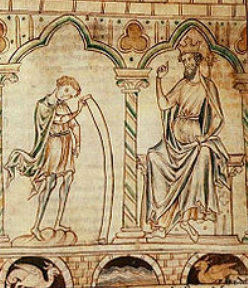

"While I was preoccupied by these matters, Walter the Archdeacon of Oxford, a man most expert in the art of oratory and in arcane histories, presented me with a certain very ancient book in the British language, which narrated in the most refined style an orderly and unbroken relation of the acts of all the kings, from Brutus the first king of the Britons to Cadwallader the son of Cadwallo." Geoffrey of Monmouth Geoffrey's Prophecy of the Two Dragons

Geoffrey of Monmouth justly takes his place among the most influential and creative minds of the Middle Ages. His pseudo-history, the Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) shaped medieval Britain's understanding of its own past like no other text. And by anyone's measure, the book was a bestseller, with 217 surviving copies still found throughout Europe. The Historia chronicles the almost two-thousand-year history of Britain's pre-Anglo-Saxon (i.e., Celtic) kings, from the foundation of Britain by the Trojan exile Brutus through the decline and fall of British sovereignty in the seventh century after the death of its final king, Cadwallader. Along the way, Geoffrey provides the first narrative accounts of Shakespeare's Cymbeline and Lear, of Old King Cole of nursery-rhyme fame, of the boy-prophet Merlin, and, most importantly, the first birth-to-death account of Britain's most famous king, Arthur. In fact, the publication of the Historia Regum Britanniae in about 1138 sparked a vogue for stories about King Arthur and his knights that flowered throughout the Middle Ages and persists to the present day. Details about Geoffrey's early life are hard to come by. He seems to have been born around 1095 in Monmouth, on the Welsh border, probably to parents of Breton origin; his family probably came to Britain from Brittany as part of William the Conqueror's forces. He may well have been educated at the priory of St. Mary's Church in Monmouth. As a young man, he found himself among the English intelligentsia at Oxford, where he was likely a secular canon at the College of St. George, right next to Oxford Castle. (Indeed, today the remains of the College are on the castle grounds.) Despite his status as a member of the clergy, Geoffrey expresses a distinctly secular worldview. His Historia bucks many of the trends of the more sober monastic chronicles of his day, and he displays a keen eye for a colorful story. His interest in worldly affairs is hardly surprising, seeing that he rubbed elbows with the rich and famous: among his patrons we can count Earl Robert of Gloucester, Bishop Alexander of Lincoln, Waleran de Beaumont, King Stephen, and even, possibly, the Empress Matilda herself. He seems to have been well-trusted by many of these luminaries, as he served as a witness to many important charters, including the 1153 Treaty of Westminster that ratified the succession of Henry II as king. His aristocratic patrons rewarded him with the bishopric of St. Asaph's in North Wales, though he seems never to have occupied his see due to unrest among the Welsh. During the years of his greatest political activity, Geoffrey somehow found the time to compose the Historia Regum Britanniae. Although he claims that his work is merely the translation of "a certain very ancient book in the British language" given to him by his associate Walter of Oxford, scholars have shown that source to be spurious: the claim to some previous "authority" was a widespread trope among medieval writers, and it often masks brash originality. As it stands, Geoffrey text is an intricate patchwork of excerpts from Gildas, Bede, and Nennius (all earlier historians), Welsh genealogical tracts and regnal lists, oral folklore from Wales, Brittany, and elsewhere, and early British saints' lives -- all pulled together and supplemented, no doubt, with ample material from Geoffrey's vivid imagination. Among the many themes that emerge throughout this rich narrative are the necessities for a strong unified monarchy in Britain and the avoidance of civil wars. These messages must have been timely indeed, for the years that followed the Historia's publication saw England plunged into years of civil discord -- the Anarchy -- under the usurping King Stephen. Later in life (ca. 1152), Geoffrey returned to the character of Merlin, whose origins and prophecies he had explored in the Historia, and composed a long poem in stately Latin hexameters, the Vita Merlini (The Life of Merlin). This poem reveals Geoffrey's further study of Welsh lore, and particularly of Welsh prophetic traditions. In it, Geoffrey describes the aged Merlin's retirement from the world after a traumatic battle, his "madness" and estrangement from his wife, and his final withdrawal to a woodland retreat in the company of two prophesying comrades: the Welsh poet-scholar Taliesin and Merlin's own sister Ganieda. The Vita Merlini was Geoffrey's last known work. He died a few years later, in 1155. His works, especially the Historia, influenced some of the finest writers of the Middle Ages, including Marie de France, Walter Map, Chrétien de Troyes, Layamon, and Geoffrey Chaucer. Further Reading

|

|